K. Michael Wilson

This essay discusses specific plot events (“spoilers”) of the novel Ibis (1985) by Linda Steele. If you are predisposed toward appreciating obscure 1980s sci-fi literature, or if you are fairly generous toward lesser known authors, I would strongly encourage you first to read the novel online before reading the essay. If you are more skeptical of obscure book recommendations, consider first reading the essay, to see whether I can convince you of this work’s artistic worth.

The ubiquity and complexity of global exchange predispose one to experience and imagine “the market” as if having character traits and volition, as if possessing “a mind of its own.” The greater a society’s market penetration, the more likely it is for ideologies to emerge that bolster these intuitions, envisioning society as not only speaking through “the market,” with art and literature as forms of expression one can purchase and consume, but speaking as “the market,” with market success a reliable communicator of general social approval.

Even among critical scholars who might otherwise “know better,” there likely remain, lurking in the unconscious, and encoded into the cultural architecture of language and thought, belief-like substances that conceive of popularity as some kind of emergent form of democracy. And even if it is not immediately obvious how to square the sentiment with materialist analysis, the idea that we remember good literature when it speaks to deep issues seems uncontroversial enough. After all, surely there’s something good in a work, if so many people like it? And isn’t it elitist to condemn popular forms of artistic expression? And how can you criticize an author for being too successful? And, besides, can’t so-called “highbrow” and “lowbrow” art co-exist?

Earlier this summer, Current Affairs released an article exploring the paradox of J.K. Rowling, trying to reconcile the capaciousness of Rowling’s literary imagination with her blinkered social and political ideology, particularly her views toward transgender people. If nothing else, the unfortunate nature of Rowling’s stances has offered the global reading public an unusually well-defined opportunity to reflect on the meaning of literature and authorship and on the social significance of literary political economies. If it is clear enough in 2024 that authors and writers are generally underpaid, it is far less clear, even in the abstract, what it would mean for an author to be overpaid. It’s easy to shrug off the question; “what would that even mean, overpaying an author?” But with vocally vile Rowling worth trillions of dollars, maybe it’s time to go “full utopia,” and to start imagining radically alternative social-provisioning arrangements. Even within the current system, if authors were paid a modest but comfortable wage, say, $80,000-$90,000 dollars a year (including healthcare), how many non-transphobic authors could fit inside one J.K. Rowling-sized portion of the global book economy?

In the long run, we are all dead, and in the long run of historical literature, it doesn’t really matter whether a book sells. Indeed, it doesn’t even matter whether a work is “published” in any formal capacity; it only matters whether it is preserved in some legible form. If you, by some twist of fate, happen upon an unpublished manuscript in a great, great grandparent’s tomb, or whatever the case may be, it doesn’t matter whether that manuscript ever saw the light of day, it’s still technically historical literature. It counts. It exists. Maybe it’ll be placed in some kind of archive, especially if historical or literary merit is observed within.

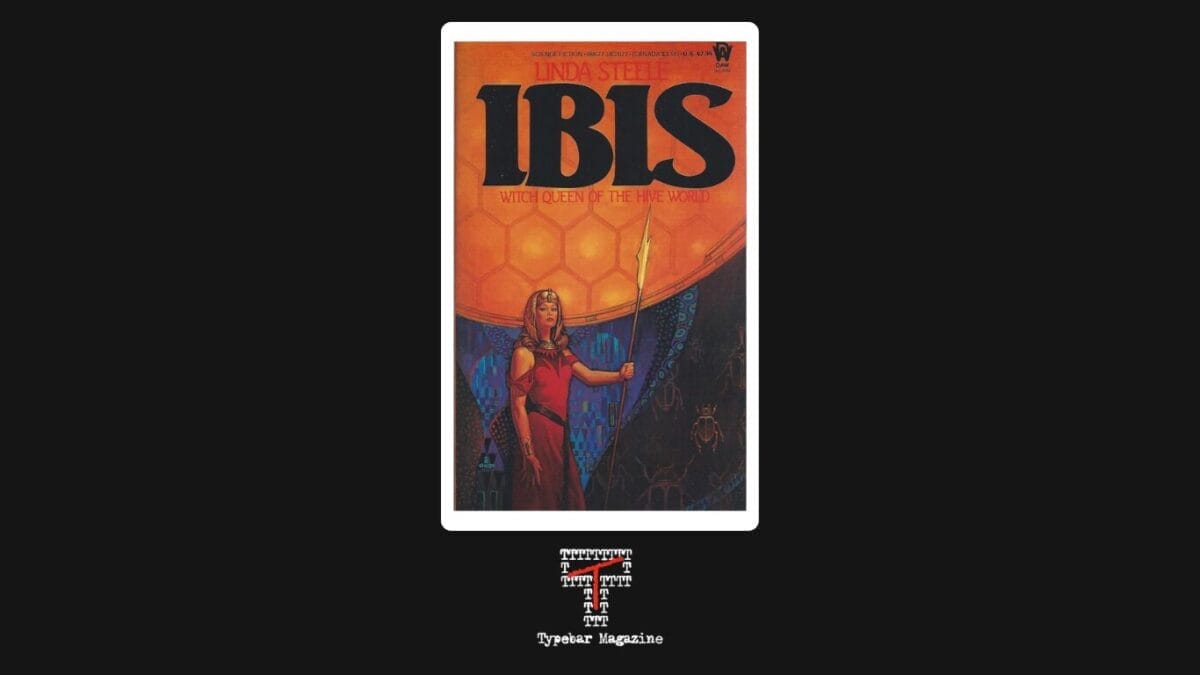

It with these material concerns in mind, the historicity of book markets and literary meaning in question, that I hope to introduce readers to Ibis (1985) by Linda Steele, a “lost work” of “lost world” literature, a mass-market paperback possessing an emotional sophistication and psychological subtlety unique for 1980s era science fiction and surprising for a work this neglected. The novel secured a nomination for the 1986 Locus Award for First Novel, ranking 24th out of 25 nominated works, and received a favorable review by Diane Parkins-Speer in the November 1985 edition of Fantasy Review, a notable, if niche, science fiction magazine that at the time was being run out of Florida Atlantic University. Steele’s novel appears never to have been reprinted, and is rarely featured in online lists, or mentioned in blog posts or essays, even those directly relevant to its subject matter. Currently on Goodreads in summer of 2024, the novel has a mere 14 ratings (one of which is my own), and 3 reviews (one of which is my own), with just 23 people currently “wanting to read” it. These figures suggest a high level of obscurity.

Before Ibis properly begins, there is an introductory quote in which the author Linda Steele describes the work in her own words. Parkins-Speer praises Steel in her 1985 review, but questions Steele’s self-description of the novel in this quote. Parkins-Speer describes Ibis as “[a]n accomplished work focusing on interspecies sex and alien sexuality,” but goes on to write, “The author states that this is ‘a science-fiction romance.’ Perhaps. I think it is rather an ironic reversal of current sexual stereotypes which also toys with the titillations of bondage and sadomasochistic eroticism in a science fiction mode.” (1985: 24) In what follows, I hope to demonstrate how both characterizations, both Steele’s and Parkins-Speer’s, can simultaneously be true.

It is probably best not to posit “romance” as a foreign entity, an “alien invader” into science fictional spaces, while still acknowledging real convergences and divergences in historical literary traditions. Outfitted with a more expansive conception of “romance,” one can easily regard all of science fiction as “romances of thought,” as whimsical ideas expressing a love for invention and inquisitiveness. This is at least partly the sense in which some late 19th and early 20th century science fiction refers to itself as “scientific romance.” As Stableford discusses in Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950, the term “romance” was often used synonymously with “fiction,” or with “fantasy” in the sense of fanciful ideas (1985: 5-7). Later in the twentieth century, the “space opera,” viz., a “soap opera” in space, would sometimes be explicitly sold as “romance,” even as the form tended to incorporate “romantic” elements merely as framing devices for masculine-coded adventures.

Global historical literature, especially but not exclusively literature from English language traditions, interacts in complicated ways with imperialism, colonialism, and orientalism. Unmapped and uncharted geographical spaces often became illicit vessels, perverse conduits for the utopian and dystopian imaginary. It is arguably to this effect that H. Rider Haggard, in writing She: A History of Adventure (1887), establishes the standard for “lost world” literature, setting his tale in the “deepest reaches” of sub-Saharan Africa, a location that he knew from personal colonial experiences but which readers are encouraged to imagine as a pristine world “outside of time” where supposedly eternal archetypes, like the “eternal feminine,” enact and reenact definitive traumas. She might be explicitly labeled an “adventure,” to be compared with works by Jules Verne and Robert Louis Stevenson, but it is also a “romance” in the more general sense being considered, and is arguably an exemplar of “romanticism” in literature. When “planetary romance” later emerged as a subcategory of “scientific romance,” it would be this “lost world” paradigm to transform, subcontinental distance finding its interplanetary equivalent.

It’s worth emphasizing that, much like the Harry Potter series (1997-2007), She: A History of Adventure was a hugely successful market event. The Wikipedia page for “List of best-selling books” has She at 83 million copies sold, to be compared with Harry Potter at 120 million and The Da-Vinci Code at 80 million. By way of global comparison, the eighteenth-century Chinese classic Dream of the Red Chamber (on which I completed my dissertation) is sometimes quoted at 100 million. Whether the market success of She reflects the work’s literary merit remains a matter of some circumspection; the critical response to She has been, to this day, deeply divided. Evading questions of artistic worth, one can at least speak confidently in the work’s depth of influence, including upon some of the most important thinkers of the early twentieth century. Notably, not only did Sigmund Freud read Haggard’s work and speak highly of it, but he also dreamt of it, one of the dreams that he chooses to analyze for his masterwork The Interpretation of Dreams explicitly referencing She in its internal dialogue and adapting imagery from the novel to serve as manifest dream content.

The basic premise to Ibis is loosely comparable to Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle. In some distant past, the galaxy was colonized by humans and humanoid beings, many of whose civilizations were lost to time. When a human starship is forced to make a crash landing on the planet Ibis 2, the crew are surprised to discover one such lost world, a planet of forest and jungle dotted with highly hierarchical humanoid civilizations reminiscent of bee hives, in which only elite female humanoids can produce offspring, and in which all male humanoids possess diminished mental capacities, are loyal, docile, and subservient, and seemingly have evolved to die upon orgasm, each thereby procreating at most once.

It’s illustrative to read Ibis as at least partly a dramatic, or “ironic” reversal, to use Parkins-Speer’s term, not only of patriarchal society in general, but of the plot conventions of She in particular. Whereas in She it is Holly and Leo who are “on the move,” “penetrating” the dark and damp domain of She-who-must-be-obeyed, in Ibis it is the native Anii, who would soon become Queen of her “nom” (viz., her hive), who is the active, seeking, “leading,” “hunting” agent. Steele takes special pains to contrast Anii’s mobility with the permanent immobility of the alien foreigners’ crash-landed ship, describing it as a “great grounded thing” that seemed as if it “had never flown, or at least would never fly again.” (5) Later in the text, after even more time has passed, the ship is described as a “dying reminder of something already fading, being absorbed into the planet,” dramatizing the novel’s thematic emphasis on burial and “accepting fate.” (196)

Anii is fascinated by the foreigners, spying on them for extended periods and marveling at how the male crew members appear, shockingly to her, sometimes to occupy positions of authority. Anii further upsets conventional gender standards and expectations by taking a special interest not in any of the stereotypically masculine men among the foreigners, but rather in the gentle and sensitive Padrec Morrissey, the plant biologist whom Anii observes risking his life to obtain an especially striking flower blossom from a high branch. This image, of course, pairs nicely with the theme of “bee hives” and “pollination,” particularly as the question of “agency,” of “lead” and “follow,” in these natural domains is sufficiently subtle, “open to interpretation” – who leads, who follows, the bee or the flower? – and, hence, well-suited for an exploration of alternate social and gender arrangements.

It’s common to dismiss a work of literature as “entertainment, not art,” if the contours of its wish fulfillment are too pronounced. While I hesitate in jettisoning the distinction, one could at least question the underlying assumption that desire, pleasure, and even “being sentient” are simple, straightforward matters easily “solved,” socially and conceptually. How precisely wish fulfillment functions in literature remains speculative partly because psychology and psychoanalysis themselves remain speculative, with any one theory or explanation needing to be taken with a grain of salt. In addition to everything else, in trying to conceptualize “science fiction romance,” one finds oneself at a crossroads of historical gender divisions in reading, which further complicates analysis, and renders the following at times necessarily speculative.

Since the treatment in Ibis of sexual assault and coercion reflects how these subjects are approached in romance literature, it’s worthwhile to locate the work within this broader historical context. Male science fiction readers less familiar with the history of romance novels might be surprised by their actual content, the requirement of a “happy ending” belying the sheer amount of pain and suffering often leading up to such an ending. The centrality of sexual assault to so many of these narratives is at times almost difficult to fathom; a plot summary of The Flame and the Flower (1972), the first modern “bodice ripper,” would read like a police report from an elaborate crime scene. It can seem at times as if scenes depicting sexual assault for female readers (reading female protagonists) have come to function analogously with “fight scenes” for male readers (reading male protagonists). What is the significance of these developments? Are sex and violence truly the events defining one’s existence? And what role has literature played in foregrounding them?

Rather than dismissing romance novels we don’t like as “pure wish fulfillment,” one is better off thinking about the vagaries of desire and fantasy, and the complex ways that fantasies distance themselves from, while still deeply reflecting, the material world, the so-called “real world.” (Sometimes, as in the case of “lost world” narratives, that “distance” is actual physical distance.) It’s not the case that fantasy necessarily presupposes plausibility. Rather, fantasy is often designed not to be; fantasy is a construction whose implausibility, whose impossibility, even, can at times lend it strength and coherence. There is, it would seem, security in knowing that the enforcement of the terms and conditions of one’s fantasy is limited to the fantasy domain. With enough formal modification, all fantasy, like “what happens in Vegas,” cannot help but remain properly contained within its special realm.

It’s probably best to start thinking in more multimodal terms, especially, I think, along vectors of identification, projection, displacement, disavowal, and so on. The standard, somewhat reductive explanation of “rape fantasies” involves disavowal; the coercion inherent to the crime of rape is said to shield, censor, or occlude the fantasy-havers own “illicit” sexual desires, which, so the argument goes, can now be “enjoyed” while simultaneously being disavowed. There are additional questions of whether not simply desire but also fear, and the excitement of fear, are motivating a lot of these narratives and readerly engagement with them. Not only that, given the historical and present-day ubiquity of women’s oppression, it’s not unreasonable to foreground romance novels as means for contextualizing, understanding, reflecting upon, and resisting oppression and unfreedom. Beyond simply depicting rape, a lot of romance novels describe what is termed “forced seduction,” rape in the sense of “the rape of Sabine women,” viz., rape, abduction, coercive pregnancy, and domestic servitude, that is, the kinds of traumas and hardships that resonate with many historical and present-day women’s lived experiences.

There is a common dynamic in romance novels, whereby a traumatic action or events will be depicted, but then its form will very quickly be “mediated.” A reader can, in this way, experience both the depiction of a charged event, as well as a “mediated” reiteration that alters and transforms the meaning of what’s just been depicted. In the case of The Flower and the Flame, less significant, perhaps, than the sheer quantity of rape is the way that the act is variously reframed and refracted. In the beginning of the novel, due to a series of miscommunications, the eventual love interest Brandon Birmingham rapes the protagonist, but then is revealed not to have known that he is raping her (i.e., he thinks that she is a prostitute whose services he has purchased). Commonly in this way, the form that the coercion takes can be seen mediated, inverted, transformed, “decaffeinated,” re-caffeinated, and so on, to various effects.

In the case of Anii’s first sexual encounter with Padrec, there are similarly mediated issues of consent, intention, and misunderstanding. Padrec has just returned from a daytrip surveying the local flora and fauna only to find the human base (viz., the crash-landed spaceship) destroyed by native Ibisians, most of Padrec’s fellow crew members having been killed in the assault. It is arguably in this moment that Anii first glimpses Padrec’s “fully flourishing humanity,” so different from the male drones of her own society, his burial of fellow crew members impressive evidence of advanced cognition and, hence, of a “capacity for ritual” lacking in Ibisian males.

Not fully approving of her nom’s attack on the human strangers, and having already from afar taken an interest in this particular “young, dark-haired,” plant-loving male, Anii quickly escorts Padrec away from the ship and from patrolling Ibisian soldiers to a nearby patch of forest, its floral floor soon to be the site of their first sexual congress. The text is silent on the extent to which Anii can control her powerful alien pheromones, leaving open the question of whether Anii could “choose” to deploy them. The text makes clear that, both for Ibisian “hive” males and for the crash-landed human males, the effects of the pheromone are strong enough to render them mentally (and, perhaps, physically) incapable of resisting sexual advances, which might make for a plausible biological feature in a species for whose males “small” and “large” deaths coincide.

Ibis is framed, then, by a rather serious consent violation, a distinctive thematic thread that is woven throughout the text. That issues of consent are so central to Ibis just as strongly as anything else bolsters the novel’s “romance” credentials. If Anii’s rape of Padrec in the forest isn’t immediately “experienced” by the reader as rape – arguably, it’s not just rape but attempted rape-murder, as Anii was under the impression that the encounter would kill him – this is no doubt a reflection of the gendered values readers are bringing to the text, values that Steele is skillfully challenging and subverting.

While many science fiction and fantasy works present gender-inverted hierarchies, the depiction tends to be in broad strokes meant for general critique, often meant to clarify why a social form is problematic or otherwise shouldn’t exist. Of the pre-war “scientific romance” works experimenting with these themes, Stableford observes that “[m]ost […] had been written by men, and most concluded that women were not equipped by nature for running the world.” (106) The average plot would feature a male protagonist’s invading a female-dominated space, gawking at its various gendered inversions, and witnessing “compelling firsthand evidence” for how this alternate arrangement is “purely illogical” and, hence, destined to fail. By the end, the male protagonist can be guaranteed to “swing into action,” reestablishing traditional gender roles and riding off into the sunset with the former Queen now his mere wife or consort.

As will be seen, Ibis’s plot arc could hardly contrast more strongly with this model, with Ibis firmly establishing itself as “science fiction romance” and not simply “science fiction” by focusing heavily on the relationship between Anii and Padrec developing in this gender-inverted context. Despite all the action, all the violence and deception, all the escaping, capturing, recapturing, re-escaping, etc. etc.—despite all of this, the meta-cognition levels in this novel are off-the-charts. You would never believe how much “discussion of each other’s emotions” can be packed into so few paperback pages, as Anii slowly learns of the cultural and intellectual potential of the crash-landed human males and attempts with Padrec to foster a relationship of mutual obligation and understanding that builds upon the physical and chemical bases of their attraction.

With Ibis, the extremity of the science-fictional climes seems only to accentuate its “romantic” qualities. The arc of Anii’s character development is unusually pronounced due to how unusually hierarchical her society has been engineered to be. The result is that Anii’s personal growth doubles as a quasi-parodical microcosm of hundreds of years of Enlightenment progress. Over the course of the novel, readers witness Anii’s single-handedly reinventing the concept of a “gentleman,” the idea, revolutionary given the inverted social context, that men are capable of critical and creative thinking and are more than just workers, warriors, and single-use disposable sex objects.

Part of the marvel of reading Ibis is experiencing the lurching awkwardness inherent to transformative psychological, emotional, and social development, an experience fortified by Steele’s steadfast refusal to make Anii more relatable and cosmopolitan. Most contemporary authors would simply be unable to resist projecting more of their own contemporary values onto the character, rendering Anii’s actions if not perfectly ethical per se then at least more bureaucratically, abstractly legible, with the effect of rounding off all the edges, leaving the story anodyne and, potentially, meaningless. Instead, Steele has rapt readers looking on as Anii repeatedly “corrects” for her various ethical atrocities by committing yet further, different atrocities, by the end of the novel developing tremendously as a character but never quite achieving a moral and ethical sense that could be consistently characterized as “modern,” let alone “progressive.”

Anii’s personal transformation is from having never conceived even of the abstract possibility of a romantic partner, having only known male humanoids incapable of higher-order sentience, to being highly attuned to Padrec’s human needs, even predicting and anticipating them, albeit highly imperfectly, and often to effect equally horrifying and hilarious. It is in this spirit of broadmindedness that Anii advises Padrec to take a human lover during her mating period, their genetic incompatibilities obliging her to find an Ibisian male for the “socially necessary labor” of repopulating the nom. The ethical basis of this action is critically undermined by Anii’s subsequent decision to go along with, as part of the xenobiologist Toroya’s human breeding (“anti-inbreeding”) program, a plan to pump pheromones into a laboratory where Padrec would be working together with Janelle McDonald, a fellow crash-landed crew member also being held captive, in effect forcing the two to have sex with each other, from which coupling a non-consensual pregnancy results.

I second Parkins-Speer’s estimation of “kink” and “S/M” undertones to the novel, although the matter is curiously difficult to assess, partly because so much of what would be classified as “kinky” activities and signifiers are directly implicated in the world being conceived and “baked into” the plot itself. Yes, there are chains, but they are being used to keep actual prisoners in captivity; yes, Anii has Padrec whipped, but as a real punishment for a treasonous crime. There is, in other words, a basic structural difference that discourages us from characterizing this work as “Sacher-Masoch in Space,” or as “Venus in Furs, but Literally on Venus,” viz., that whereas Venus in Furs or de Sade’s 120 Days involves imagining a world-within-the-world, a quasi-playacted “slave society” within a value-abstracted “bourgeois order” where various inversions and perversions can occur, Steele’s Ibis, similarly to Haggard’s She or to depictions of “Women’s Country” in Journey to the West and in Li Ruzhen’s Flowers in the Mirror (1827), involves finding a world-beyond-the-world in which these inversions and perversions can take place.

By being within, rather than “without,” a greater social structure, kink and S/M can sometimes seem to involve inherently “performative” forms of cultural expression, this nested quality lending itself to irony and reflexivity, and requiring special language that can distinguish representations from representations within representations, and dreams from dreams within dreams. The strange effect is that, whether it’s Venus in Furs, which has clear literary merit, or 50 Shades of Grey, there’s a general tendency for kink and S/M activities to become themselves the subject of the story, even arguably the “problem” of the story, rather than being merely an identity vector secondary to other plot concerns and thematic developments. Perhaps, though, this sort of dynamic shouldn’t seem so strange to science fiction readers? After all, if science fiction is the depiction of new “technology” and its effects on society, and if “technology” is defined broadly enough to include “social technology” (e.g., courtship rules, marriage customs, etc.), one might reasonably conclude that all kink and S/M stories – indeed, that all “romances,” traditional or otherwise – are, by default, exercises in, and “subgenres” of, science fiction.

Comparison with mainstream romance novels can further elucidate the plot structure of Ibis, especially the way in which the novel systematically removes the mental, physical, social, and spiritual blockages preventing Padrec from committing fully to Anii. Though Anii captures and recaptures Padrec over the course of the novel, only by escaping her fully, and by completely discharging his social debt to his fellow humans by releasing them from slavery and captivity (even leaving them a “genetic contribution” by way of Janelle’s baby), is Padrec able finally to return to Anii and to submit himself completely to her love and dominion. Echoing the “mediations” discussed above in terms of The Flame and the Flower, the basic gesture involves the reiteration of a formal element or plot point in a way that radically changes its meaning and significance.

These back-and-forth dynamics, combined with the novel’s forced seduction themes, are oddly reminiscent of the classic bestseller The Sheik (1919) by E.M. Hull. In The Sheik, the kidnapped protagonist Diana eventually falls in love with her abusive kidnapper, who realizes the depth of his own feelings for her when she is kidnapped from him (viz., in the reduplicative moment when she is re-kidnapped, that is, when she is kidnapped from her kidnapper). Having later recovered Diana but having realized the damage he’s done in his racially motivated mistreatment of her, the Sheik, in an expression of his love, releases her from his control, which, in turn, allows Diane freely and willingly (after a rash suicide attempt is narrowly averted) to recommit herself to him, this time in a significantly more loving and more equal relationship.

What about Ibis? Does it have its own “happy ending”? Here, as elsewhere, the devil really is in the details. Padrec, having freed the remaining humans from enslavement, and himself on the brink of escaping together with them, decides at the last moment to commit himself to Anii and return to the nom, despite whatever punishments might await. If the couple’s “togetherness” is the sole or primary criterion, well, not only are Anii and Padrec “together at the end,” there remain almost no traces of non-native human civilization to remind Padrec of his “former life.” Anii has had destroyed or replaced just about everything and everyone, including Toroya, who Padrec still considers at least partly a friend, who was not involved with the escape plan and who Anii in anger, and partly for strategic political reasons, has murdered in place of Padrec for Padrec’s crime, with Padrec watching on in horror. Needless to say, I’m interpreting these actions as further evidence of Anii’s somewhat “incomplete” moral and ethical development. In a jaw-dropping denouement in which Padrec must put to rest his former life, Anii grants Padrec the right to bury Toroya, but he must do so this time attended by scores of unsympathetic guards, while still, as before, only using his bare hands.

Ibis is a remarkable read, its obscurity a much-needed reminder of how inconsistently, if at all, market success reflects artistic worth or even, for that matter, long-term readability. Is your average reader in 2024 going to enjoy She as much as Freud did at the turn of the twentieth century, and, if not, what does this reevaluation say about the novel’s artistic worth? In 50 years, will anyone still be reading 50 Shades? Why not? And does it matter? Or, to ask a similar question, is not an alternate reality 1980s imaginable, one in which Ibis were a smash hit? Is there really no alternative? Imagine if Reagan were in the habit of giving out Obama-style book recommendations, and recommended this work? Is it so inconceivable?

Maybe, no matter what, status quo patriarchal values would have had too much of a dampening effect. It’s notable that, historically, the truly “viral” literary kink offerings seem overwhelmingly to be in the “M/f” rather than the “F/m” mold. Venus in Furs never sold at levels comparable to She or other major bestsellers, even despite choosing the safe route, plot-wise, and having the text in the end disavow female dominance, Severin “snapping out of it” and deciding henceforth to dominate women, rather than letting them dominate him. Similarly, while She depicts a matriarchal civilization, it does not offer an alternate social arrangement per se, but simply presents the equivalent of a dream vision, notably one in which “female yearning” is eternal and female rule is self-destructive. Perhaps to this day Ibis remains too radical for not having, by the end of the novel, its female-led civilization going up in flames.

If there must be yearning eternal, let it be my own, for emotionally and psychologically sophisticated science fiction. Maybe this will mean importing genre conventions and thematic sensibilities wholesale “from without,” or maybe this will mean tracing historical currents and crosscurrents already active just beneath the surface, excavating works whose future visions were slightly too “ahead of their time” to have been properly “registered” in the genre’s historical memory. Given the rising visibility and social standing of queer identities, it seems possible that the social “need” for strictly segregated reading patterns will diminish and further genre transformations will result. Perhaps liminal (“mediated”) genre forms like “sci-fi romance” (or, more recently, “horror romance,” or “horromance”) will be at the forefront of the development of more nuanced forms of gender expression.